Integrating VHR Imagery and GPS collar data to map Andean bear movement and conflict zones

Authors | Ruthmery Pillco Huarcay (Conservación Amazónica) and Japheth Kimeu (CCF)

- State of species

- Ecosystem management

-

Little is known about the elusive Andean bear’s movements and behaviour in its remote habitats. This first-of-its-kind study reveals drivers of bear movement, crucial for mitigating human-bear conflict.

-

The Andean bear has lost over 75% of its historical range and is increasingly threatened by habitat loss, predation on livestock, human-wildlife conflict and expanding human activity.

-

High-resolution 30cm Pleiades Neo satellite imagery and GPS data from six collared bears were used to overlay bear movement data, with fine-scale habitat maps and human pressures across 953 km² of the Manu Biosphere Reserve.

-

Bears primarily used forests and shrublands near rivers, avoiding densely populated areas, and overlapped with livestock in grazing shrublands and grasslands— revealing key conflict hotspots.

-

Findings are guiding community-led conservation, including habitat restoration, creation of wildlife corridors, and targeted conflict mitigation led by local leaders and indigenous women.

Objectives

1. Characterise Andean bear movement, habitat use and livestock interactions to inform species and habitat management plans.

2. Identify high-risk areas and mitigate conflict between humans, livestock and bears.

3. Create maps to support community engagement and education to reduce conflict

Introduction

Little is known about the movement and behaviour of the elusive Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus), particularly in the remote and inaccessible regions it now inhabits. Yet understanding its behaviour is critical. The Andean bear has been particularly hard hit, experiencing one of the most severe range contractions recorded for any large carnivore—an estimated 75.2% loss of its historical distribution (Wolf & Ripple, 2017). This dramatic decline has left it among South America’s most threatened and least-studied large mammals, highlighting an urgent need to uncover what drives its movements and how it interacts with a rapidly changing landscape.

As an adaptable, omnivorous species, the Andean bear can persist in a remarkable array of environments, from tropical dry forests to high Andean grasslands. However, its habitat use is closely tied to the availability of forest cover, water sources, rugged terrain, and critically, the level of human disturbance within the landscape. In one area, where patrolists allow livestock to roam freely, observed behaviour has revealed surprising interactions between bears and cattle: cows wandering into forested ravines have reportedly been pushed from cliffs, by the bears, after which the bears cache the carcasses in trees, presumably to secure them from scavengers and other predators. Although anecdotal, such events highlight the complexity of human–wildlife interactions and how altered landscapes may shape bear behaviour in unexpected ways.

Rapid land-use transformation, including agricultural expansion, intensified human presence, and retaliatory poaching linked to crop and livestock damage, continues to jeopardise the species’ long-term viability. Furthermore, the bear’s current distribution is highly fragmented across the Andes Mountains, especially as a result of mining, preventing individuals from moving freely across the landscape and disrupting historic dispersal routes essential for gene flow. Such fragmentation isolates subpopulations, which can lead to reduced genetic diversity, increased inbreeding, and a diminished capacity to adapt to environmental change or emerging threats.

Study Area

This study is set in the Kosñipata–Carabaya Key Biodiversity Area of the Manu Biosphere Reserve in southeast Peru, a region positioned where the Andean and Amazonian watersheds meet. Recognised for its remarkable biodiversity, it supports the Andean bear alongside other threatened species such as the dwarf deer (Mazama chunyi), puma (Puma concolor), Andean fox (Lycalopex culpaeus), and Andean cat (Leopardus jacobita).

Forest loss has accelerated over the past two decades, averaging around 11 km² per year. Major drivers include wildfires, agricultural conversion, illegal logging and illegal mining.

Figure 1: Deforestation of the Andean Bear habitat (C) RedPrensaVerde

Methodology

Resource Selection Function (RSF) Model

The analysis utilised very high-resolution (VHR) satellite imagery from Airbus Pleiades Neo, with a spatial resolution of 30 cm, covering a total area of 953 km². The imagery was captured between October 2024 and June 2025, providing a detailed and up-to-date representation of the study landscape.

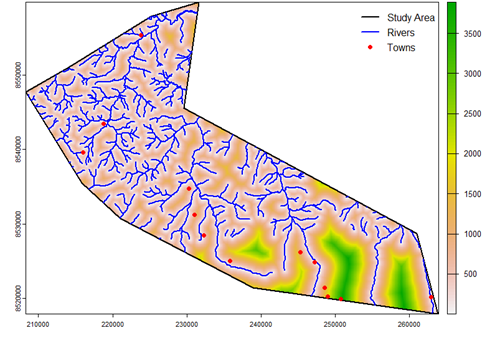

In addition to the satellite imagery, ancillary vector data were incorporated, including rivers, towns, and protected areas, obtained from the National Database of Peru. These datasets provided essential contextual information for habitat and anthropogenic features across the study area.

All raster and vector datasets were uploaded to Google Earth Engine (GEE) for preprocessing and analysis. Individual image tiles from Pleiades Neo were mosaicked to create a single continuous raster image of the study area. This mosaicked image served as the base for landcover classification, distance calculations, and resource selection function (RSF) modelling, enabling spatially explicit assessment of bear habitat use and environmental predictors across the entire landscape.

Analysis

Landcover Classification

To characterise habitat availability within the study area, we performed a landcover classification using Pleiades Neo high-resolution satellite imagery. Based on spectral embeddings and ancillary data, we distinguished three primary landcover classes: forest, shrubland, and grassland. The classification accuracy was assessed visually and through overlay with ground-validated points, confirming that the main vegetation types were captured effectively.

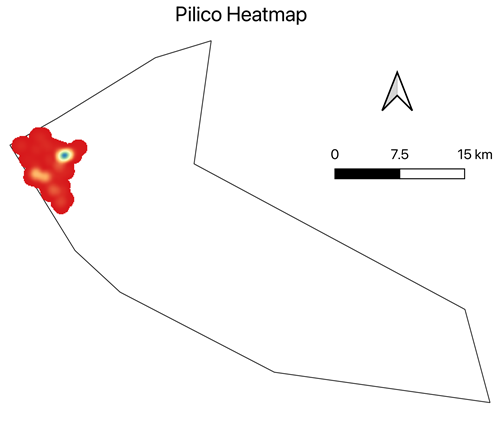

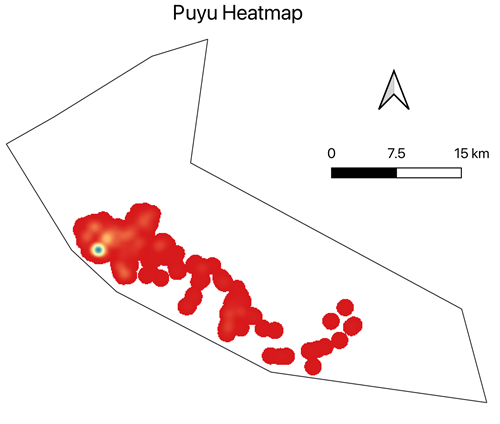

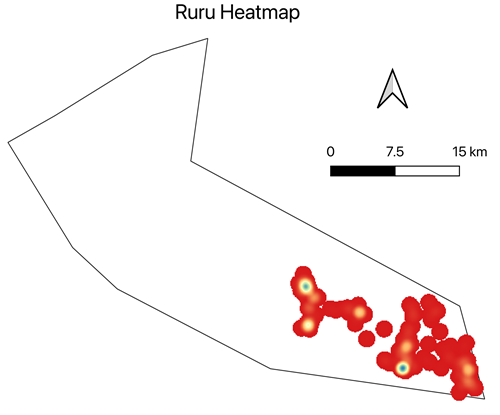

Bear Movement Data

To examine habitat use, we overlaid GPS collar data from six individual bears onto the classified landcover map. Each bear’s movement points were plotted against the landcover classes, revealing distinct patterns of habitat utilisation and bear behaviour. We also analysed their movement in both day and night across the three major habitats in the study area.

|

|

|

|

|

|

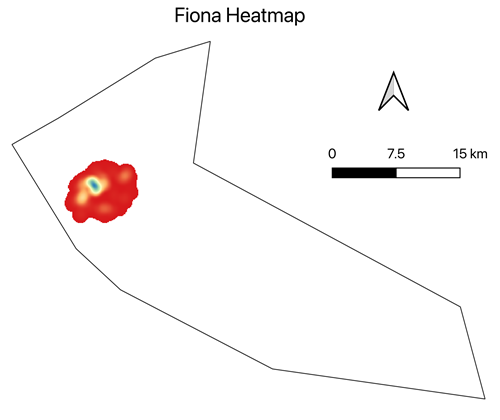

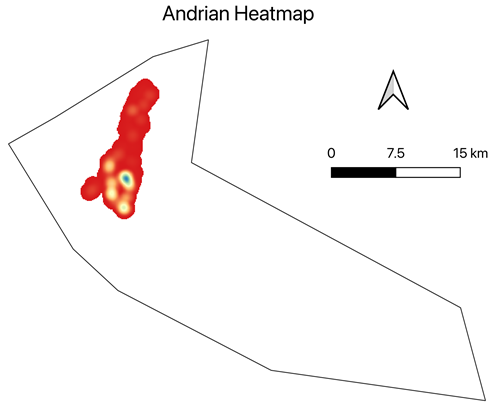

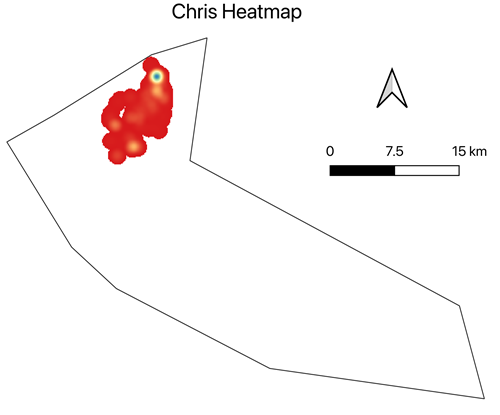

Figure 2: Heat maps of GPS locations for individual collared bears

Distance layers were also generated for each point, distance to rivers and distance to towns, derived from river and town shapefiles. These covariates provided additional environmental context, capturing bear accessibility to water and anthropogenic disturbance.

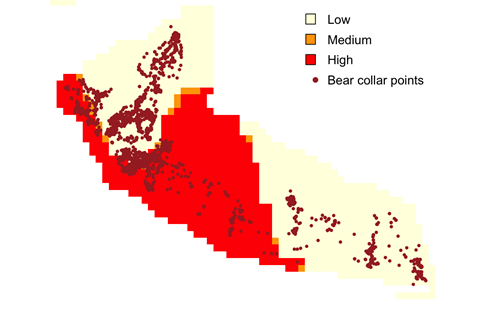

Figure 3: Heat map of combined GPS locations from all collared bears, illustrating spatial patterns of habitat use and areas of overlap among individuals

Habitat use modelling

We fitted a binomial mixed-effects Resource Selection Function (RSF) using the glmmTMB framework to quantify the effects of landcover type, population density and proximity to rivers and towns on habitat selection. The model included a random intercept for each bear to account for repeated observations and individual variation.

Results

Bear movement

Analysis of the collar fixes shows that bears predominantly use forest habitat both during the day and night. During the daytime, 62.7% of all fixes occurred in forested areas, followed by grasslands (27.1%) and shrublands (10.2%). A similar pattern was observed at night, with 61.9% of fixes in forests, 26.4% in grasslands, and 11.8% in shrublands. Overall, forest accounted for the highest proportion of use (4,107 fixes out of 6,595), indicating that it is the primary habitat preferred by the bears across the 24-hour cycle. Grasslands were used second most frequently, while shrublands were used the least. These findings highlight the importance of forest habitat for the daily and nightly movement and resource use, but they also reflect the species’ dietary ecology. The Andean bear has one of the highest proportions of plant matter in its diet among all ursids, relying heavily on vegetative resources found within forested environments. In high-Andean grasslands such as Punas and Páramos, terrestrial bromeliads of the genus Puya represent a key food resource, which may explain the secondary but consistent use of grassland habitats detected in the tracking data.

Table 1: Habitat use by collared bears across a 24-hour cycle, highlighting strong reliance on forested areas

|

|

Forest |

Shrubland |

Grassland |

|

Day |

63% |

8% |

29% |

|

Night |

60% |

14% |

26% |

Resource Selection Function (RSF) Model

The results indicate that landcover type strongly influences space use. Relative to forest, shrubland was selected more frequently (β = 0.64, p < 0.001), while grassland showed no significant difference (β = 0.05, p = 0.36). Among continuous predictors, selection probability decreased with increasing population density (β = -0.28, p < 0.001), distance to rivers (β = -0.39, p < 0.001), and distance to towns (β = -0.12, p < 0.001). These results suggest that the species prefers areas closer to water sources, lower human density and shrubby habitats.

Figure 4: Influence of land cover (forest, shrubland and grassland) factors on bear space use

| Distance to rivers | Distance to towns | Population density |

|

|

|

Figure 5: Influence of environmental factors on bear space use

Predicted relative probability of use

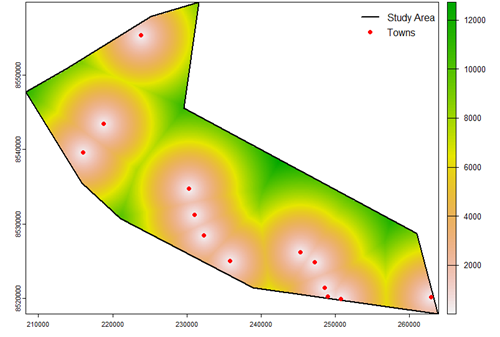

Using the fitted RSF model, we generated a continuous raster of predicted relative probability of use. Values range from 0.5 to 0.8, reflecting areas of low to high likelihood of selection. High probabilities were concentrated in shrubland patches near rivers, where human presence was low. Forest areas with low population density also showed moderate selection, whereas areas far from rivers and close to towns had the lowest predicted use.

Figure 6: Relative probability of habitat use

Visual inspection of the RSF maps indicates that the species’ spatial distribution is strongly influenced by a combination of land cover types and proximity to water and negatively affected by human presence.

Conclusion

The integration of high-resolution satellite imagery, ancillary spatial data and GPS collar information has provided a detailed, fine-scale understanding of bear habitat preferences within the study landscape. This analysis offers Conservación Amazónica a framework to inform habitat protection, conflict mitigation and land-use planning, particularly in areas where human activities overlap with key bear habitats.

By identifying zones of high bear use that coincide with human activity, Conservacion Amazonica can strategically prioritise interventions to reduce habitat encroachment. Shrubland and grassland areas commonly used for cattle grazing emerge as potential hotspots for human-wildlife conflict. Implementing targeted outreach, grazing management strategies, and community engagement in these areas can help mitigate conflicts and safeguard critical bear habitats.

Overall, this study highlights the value of combining high-resolution remote sensing with movement ecology to support evidence-based conservation planning in the Manu biosphere, providing actionable insights for both habitat management and community-oriented conflict reduction.

Conservación Amazónica - ACCA

Use science, technology and strategic actions to conserve and protect more than 5 million hectares of the Amazonian Andes in southern Peru.